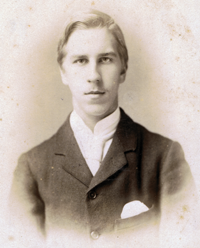

Thomas Dunhill (1877 – 1946)

Thomas Dunhill (1877 – 1946)

a short biography

Thomas F Dunhill is widely remembered for many delightful pieces written for those learning to play the piano. His contribution to the educational repertoire was extensive, with works published by several companies, including the Associated Board (ABRSM) which still uses his compositions after nearly 100 years.

Much less familiar are many fine compositions across genres that include chamber music and orchestral works, solo pieces for piano, organ and other instruments, song-settings and choral works, and scores for light opera and ballet.

Tom’s work as a composer was continuous, from the mature 21-year old student’s first chamber work at the Royal College of Music in the 1890s, through to his final works of the 1940s. By his death his Opus numbers exceeded 100, excluding small educational pieces that run into hundreds.

Considering the truly astonishing period of change through which he lived, his 50-year composing career was one of near-unbroken continuity, spent almost entirely at the epicentre of the English music scene, in London where he had enjoyed his early and extended musical education.

As a 13-year-old in 1890, he experienced the first run of Gilbert & Sullivan’s The Mikado. In 1905 he found himself discussing his own work with Sir Edward Elgar over breakfast at the Three Choirs Festival in Worcester.

Over the next few years he attended concerts in London conducted by Arnold Schoenberg and Igor Stravinsky. And by 1930 he was incorporating saxophones and muted trumpets into a jazzy comic opera called Something in the City. Even in 1945, he was still busy composing, while teaching for a second period at Eton College.

• • • •

Tom was born on 1st February 1877, the fourth child of businessman Henry Dunhill, who sold equipment for horse-drawn transport, before moving into accessories for motor cars.

Downstairs at the family home in Swiss Cottage his mother, Jane, ran a small music shop. It was here that Tom first encountered the harmonies that opened his ears to music. In later life he recalled the set of chords from Handel’s Scipione march, regularly played by the shop’s piano tuner: “the loveliest chord progression imaginable”.

It was probably his mother who first taught Tom to write music and play the piano. By the age of twelve he and his life-long friend, James Findlay, were busy emulating their heroes Sullivan and Gilbert, writing small operas for their model theatre. It was an occupation that stood Tom in good stead later in life. The family moved to Kent, but Tom continued to take piano lessons from a Mr Kennedy in London.

He must have shown great promise because he was entered for the Royal College of Music at just 16, and immediately accepted. Its director was the much-loved Sir Hubert Parry, under whom the eminent Charles Villiers Stanford taught composition.

As well as composition classes with Stanford, Tom studied piano and harmony. His teachers Walter Parratt and Franklin Taylor both had excellent pedigrees: Taylor had studied with Clara Schumann, and Parratt was Master of the Queen’s Music. Frederick Bridge, composer and organist at Westminster Abbey, taught the art of counterpoint.

Tom was encouraged to take up the bassoon to augment the college orchestra and there were also occasions when Dunhill, Vaughan Williams and Holst formed the percussion section along with Martin Shaw, a fellow composition student, who recalled this in his memoirs.

While Mozart, Beethoven and Brahms provided the dominant musical underpinning, RCM students eagerly absorbed the works of contemporary continental composers – and the Englishman Henry Purcell whose bicentenary was celebrated in 1895.

The name of Sullivan, however, was all but taboo within the college: his comic operas were judged to have compromised his talents as a serious composer. Tom must have had to suppress his high regard for light opera over the seven years he spent as a student.

Despite his youth, Tom’s progress at the RCM was swift. At the end of his first period of study, he won an Open Scholarship to extend his study for a further three years. Two years later he received a Tagore Gold Medal awarded to ‘the most generally deserving pupil’

Completing his studies in 1899, Tom became assistant music master at Eton College, Windsor. While here he started to develop lectures for a variety of audiences, and a series of talks were later broadcast by the BBC. He was at Eton for six years before being welcomed back to the RCM, this time as a teacher, of harmony and counterpoint, and later of chamber music.

From 1905, while providing a constant stream of new compositions for publication, he was employed by the ABRSM to undertake examining tours, first in Australia and New Zealand, and later to Jamaica and Canada, as well as in Britain. A few years later he took over selecting all the piano music for the Associated Board exams.

In 1907 he inaugurated the Thomas Dunhill Chamber Concerts, in London, to support the work of new, mainly British composers, such as William Hurlstone and Samuel Coleridge Taylor. The series continued for several years: a “most exemplary and useful idea”, commented The Times.

In the same year, Tom’s brothers Alfred and Herbert started the Alfred Dunhill enterprise that led by the 1920s to commercial success on both sides of the Atlantic, retailing ‘smoker’s requisites’.

Tom wrote a number of books. Chamber Music, published in 1913, was for many years a standard work for students. Two slim volumes, Mozart’s String Quartets, were published in 1927 and Sullivan’s Comic Operas the following year, containing a forceful defence of Sullivan’s much-derided reputation. He also wrote a fine critical biography, Sir Edward Elgar, published in 1938, four years after Elgar’s death.

A highlight of 1912 was a performance of his song-settings of poems by W. B. Yeats, The Wind among the Reeds, performed by the Royal Philharmonic Society with tenor Gervase Elwes. One of these songs, The Cloths of Heaven, has been performed and recorded since by many distinguished soloists.

In 1914 Tom married Molly Arnold, a great-niece of poet Matthew Arnold (John Ireland, Tom’s contemporary at the RCM, was best man at the wedding). Molly was a Cambridge classics graduate, then studying piano and cello at the RCM, and taking Tom’s harmony and counterpoint classes: a long and happy marriage might have been in prospect, and Tom was welcomed into the highly cultured Arnold family.

Tom and Molly moved to Notting Hill Gate, along with the Steinway grand piano they received as a wedding present. They started a family: sons Robin and David were born in 1915 and 1917, daughter Barbara in 1921.

When the 1st World War started, Tom joined a volunteer unit, the Allied Artists’ Force. When formally enlisted in 1916, he became a bandsman in the London-based Irish Guards, for which he had to brush up his college bassoon skills.

The war provided Tom with time for musical composition, and over three years he wrote his Symphony in A minor. According to Martin Yates, conducting the symphony for a recording with the Scottish National Orchestra, the slow movement is “one of the loveliest I have ever heard”.

By the early 1920s, although he had largely escaped the trauma of war, Tom had adjusted to the fact that the Victorian and Edwardian cultures that had shaped his musical education and early professional practice, had been literally swept away by a torrent of modernism. Increasingly, it seems, he turned his attention back to his first love, that of musical theatre.

Tom returned to teaching at the RCM. Among other remunerating activities, he was also sought-after as adjudicator at regional music festivals that were growing in popularity. Meanwhile his one-act opera, The Enchanted Garden, was performed in 1921 at the RCM, winning a prestigious Carnegie Award.

He continued to work as an examiner and to give lectures. Among less conspicuous responsibilities, he became a director of the Royal Philharmonic Society’s concerts, Dean of the Faculty of Music at London University, and attended meetings of what would become the Performing Rights Society. He also sat on the editorial board of a magazine Music & Youth, aimed at younger music students.

It is not surprising that Tom suffered periodically from overwork, and there were times in his life that he had to take enforced rest. However, it was Molly who was cruelly struck down, with tuberculosis. In 1929, after several years’ infirmity, she died while staying in Italy. In her place a nanny, Miss Wendy Moon, had come to stay. She remained with the family for 18 years.

In 1928 Tom was approached to work with well-known writer A P Herbert who was writing the libretto for a comic opera, Tantivy Towers, to be produced at the Lyric Theatre, Hammersmith. The show was a substantial success in 1931, with rapturous press coverage. It ran for several months before transferring to the West End and local theatres.

Tom continued to write music for the stage, but not with the same commercial success. Meanwhile his output of compositions for piano, voice and instruments continued. Several of these, especially for wind instruments, remain popular in recitals today.

When the 2nd World War broke out, Tom was still teaching at the RCM, and he also returned to teaching at Eton. In June 1940 he received an honorary doctorate from the University of Durham.

There were still some examining tours in Britain. On one of these, he stayed in Scunthorpe with a ‘very charming teacher’, Isobel Featonby. She was 38, and he 65. They were soon engaged, and were married by the end of the year. She joined him on the staff at Eton, where she was a popular piano teacher until her retirement in 1970. Tom died in 1946, and is buried at Appleby, near Scunthorpe, where his headstone bears the inscription Maker of Music - a phrase he apparently chose himself.

Paul Vincent, Crediton, September 2011 All comments, corrections, and suggestions for improvements to this essay are welcome:pv@eclipse.co.uk